Wednesday, 5 August 2020

You can't compare apples to oranges

Environmental award-winning horticulture farming business Woodhaven Gardens is finding a positive pathway forward in a regulatory ‘no man’s land’.

From the north side of Otaki up to Shannon, you will find Woodhaven Gardens thriving in a frost-free microclimate that gets plentiful and consistent rain. The multi-generation family business prides itself on growing fantastic fresh and healthy produce that supplies our supermarket shelves, keeps Kiwis fed and a community employed.

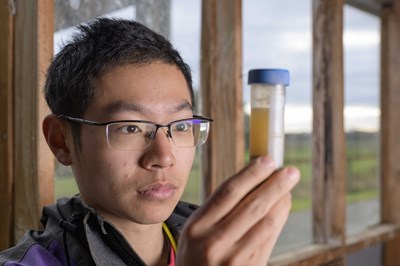

Jay Clarke, son to Woodhaven’s founders John and Honora Clarke, saw the challenges market gardeners were facing with environmental compliance and decided to rejoin the family business, having cut his teeth overseas in business development.

“There was a huge gap between industry best practice and what some regulators were wanting from the industry, which wasn’t going to be met if we still wanted to grow vegetables,” says Jay.

“The biggest challenge for us is we don’t have a viable regulatory pathway to consent that allows vegetable growing to occur in our region,” he says.

“So, when we are investing in environmental mitigations and technology, we have no certainty that our investment will allow us to continue to operate. It doesn’t give you a lot of confidence when you are working with high-value land with a high input and output system.”

Jay says getting people to understand the fundamentals of vegetable growing and the difference between that and dairy or sheep and beef farming is very difficult. “We’re producing 50 tonnes per hectare that is going to market, with only tiny losses per tonne of food produced.”

"We’ve reinvented the way we grow vegetables and farm full stop."

Recently winning the Horizons Supreme Ballance Farm Environment Award was a goal for the business and has been well earned even if unexpected.

“We didn’t think we had a shit show to be honest,” Jay says with a laugh. “By comparison to sheep and beef and dairy we don’t have the visual environmental components to show, such as riparian planting; it was hugely satisfying.

“We’ve learnt a hell of a lot from the process by talking to our community and stakeholders and focusing on what was important to them.”

Jay says rather than focusing on achieving a specific number, they have been able to come together and achieve the right outcomes for their business, community and the environment.

“We looked at the common-sense things we could do as farmers, such as always aiming to leave the roots of the preceding crop in the ground, whether it's a production crop or a catch crop. The principle being to always have a root in the ground to soak up any excess moisture or nutrients that can be lost to leaching.”

The cost of sustainability

While the low hanging fruit can make you the easiest wins, Jay says it’s not always the most cost-effective.

“We spend $600,000 a year on environmental compliance and have one person employed full time just to do the quick N tests, plus our environmental manager and myself working on sustainability. If you include the additional land we need to lease due to retiring land, the equipment cost – GPS- controlled traffic tractors, custom fertiliser spreaders and travelling irrigators – the investment is huge.”

Jay attributes their progress at Woodhaven to taking some pretty big leaps in capturing information and technology.

“We’ve reinvented the way we grow vegetables and farming full stop. There’s a huge amount that’s changed on the farm, such as quick nitrate testing where we test the soil three times in a production cycle. Once before we plant the crop, again before any subsequent addition of fert, and again when the crop has finished, so we are able to monitor the nutrients in the soil to keep between 20-40 units of N in the soil. This is important because once the crop is at a certain point, covering the ground, you can’t get back onto it to reapply.”

With GPS, Woodhaven is able to run controlled-traffic farming (travelling irrigators and custom-built fertiliser spreader) leaving the soil less compacted.

“We’ve reinvented how we spread fert,” Jay says. “Rather than broadcasting over 12 beds of direct-drilled crops we realised we could save a lot of money and nutrients by inventing a single-bed applicator. We built an attachment that went on the back of our spreaders’ Vaicon chutes that scatters the fert like it would if we’d broadcast it. While we have to do 12 passes now instead of one, using the side-dressing chute, it is far more precise.”

“When sustainability was originally coined it was multi-faceted. We seem to have lost that by only focusing on one outcome that has perverse effects on the market.”

You would think all this would be enough but there’s more to Woodhaven’s sustainable approach.

“We’ve gone beyond the one metre [sediment trap] strip requirement and put five metres of ryegrass between the tracks and the drain. A trial on our farm saw that there was no sediment loss after 1.5 metres. We also use catch crops between harvesting crops, where we direct drill ryegrass if we’re going to be more than 10 weeks before replanting the crop.” Jay says the ryegrass picks up the nutrients that the mulch of the harvested crop releases. They then harvest that grass to sell and rotary hoe the rest into the ground before replanting the new crop. “Basically, there’s always something in the ground taking up the nutrients left behind.”

The biggest reduction in nutrient losses however has come from retiring 20% of the farm by retiring the 13th bed (1.5m) on each plot for the tractors to use as a tramway. It also saved the business wasting crops and inputs that the tractor would have driven over.

All their efforts have resulted in a 47% reduction in nutrient losses, which Jay says has been hugely rewarding for the team.

“We employ 250 people from our community, providing them with a lot of opportunities and development, which is a big part of the joy we get from being market gardeners.”

For Jay a big part of sustainability is open communication with stakeholders and he wants to close the communication gap between farmers and regulators with a higher level of authenticity and transparency.

“When sustainability was originally coined it was multi-faceted. We seem to have lost that by only focusing on one outcome that has perverse effects on the market. There’s been some real gaps in the past between the science and growers in measuring the nutrient loss or value of a product versus what the market wants. We must focus on all three aspects of sustainability (economic, social and environmental) if we are going to find workable solutions.”