Monday, 15 February 2021

Protein: The future of sustainable food production

There is no doubt that the world faces a major challenge in food production and environmental sustainability. It is estimated that the world needs to produce 70% more food by 2050, and not just more food but nutritionally better food.

If such a target isn’t daunting enough, it is particularly so when viewed against the appalling statistic that close to one billion people globally already suffer from protein/energy malnutrition. Children are the most visible victims. Perhaps somewhat perversely, at the same time there is a worldwide obesity epidemic, the so-called ‘lifestyle’ diseases. Central to all of this is dietary protein that supplies the body with amino acids, essential for cellular, organ and muscle function and for the maintenance of a healthy, lean body mass.

The most cost-effective way to meet the nutrient needs of a person is through a diet containing a mixture of plant-based and animal-based foods. Animal-based foods such as milk, meat, eggs and fish are rich sources of protein and New Zealand’s farming sector has a comparative advantage when it comes to animal protein production. It is my belief that New Zealand’s relatively efficient production of animal proteins will continue profitably well into the future. Plant-based foods are equally as important as animal-based foods, uniquely supplying nutrients such as vitamin C and plant fibre. The focus should not be on plant or animal, but rather on plant and animal.

It is clear that in producing food for 2050, much consideration will need to be given to the supply of dietary protein. There will be an increasing global demand for sustainably produced protein and with this the concept of ‘protein quality’ will become an important consideration.

Not all food proteins are equal nutritionally when it comes to providing the essential amino acids. In general, plantbased proteins are of lower quality than animal-based proteins, having lower amounts of the key amino acids and being less digestible.

Quality not quantity

Quite recently a new scoring system for describing food protein quality has been recommended for international use1. The new score for protein quality is called DIAAS (Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score), and is based on state-of-the-art science, much of which was conducted by New Zealand’s Riddet Institute, a Centre of Research Excellence (CoRE) hosted by Massey University. A DIAAS value of 1.0 would mean that all that protein would be absorbed and be able to be utilised by the person, whereas a value less than 1.0, e.g. 0.5, would mean that only a fraction of the ingested protein, e.g. 50%, would be absorbed and used. A DIAAS value greater than 1.0, e.g. 1.3, would mean that the protein supplies excess, e.g. 30% more of the required amino acids, which would be a protein of excellent quality and able to complement the lower amounts of amino acids supplied by poorer-quality proteins.

It is clear from Figure 1 that animal-based proteins are all excellent sources of amino acids, and generally superior in this respect to plant-based proteins.

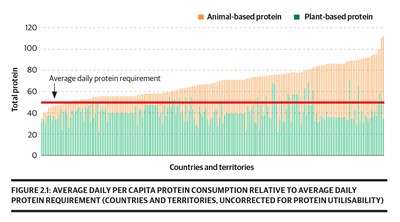

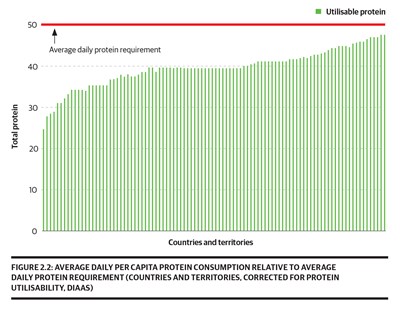

The DIAAS score, and dietary food protein quality in general are crucial to allow for an informed debate about future food production. Simplistic analyses around food protein production that don’t take into account often very sizeable differences among foods in their protein quality can lead to wrongful and misleading conclusions. An example of such misleading rhetoric is given in Figure 3: "Fake news". When considering the differences in quality between plant-based and animal-based proteins and the fact that many animal-based proteins are highly competitive economically, on a cost per key nutrient basis, this grand claim is simply not sustained. Another misleading claim is that the average person in most countries around the world consumes more than enough protein, because it doesn’t take into account the protein quality.

"Fake news"

Such claims, commonly found in the literature on sustainable food production, along with the average per capita protein consumption levels corrected for protein quality (DIAAS) referenced in Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.2. The claim that protein is generally oversupplied is shown to be completely flawed when differences in protein quality are corrected for. Therefore, reducing animal production would likely have dire consequences.

Factoring-in protein quality is also critically important when assessing claims about sustainable protein production. Figures 4.1- 4.4 show calculated freshwater use and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for food protein production, given on the conventional basis of per tonne of protein produced in Figure 4.3 and 4.4, or on the correct basis providing for a protein quality effect (lysine)3 as shown in Figure 4.3 and 4.4, providing some very different conclusions.

On the standard basis of expressing the water footprint, milk production is deemed to use 54% more water than wheat production (Figure 4.1). However, upon reanalysis wheat is the major user of water, with milk production using some 60% less water (Figure 4.2). For GHG production the conventional analysis shows rice and maize producing much lower emissions per tonne of protein produced compared to the animal products (Figure 4.3). However, after adjusting for the effect of protein quality, eggs and pork produce relatively lower amounts of GHG (Figure 4.4).

The conclusions reached are profoundly influenced by accounting for the large differences in protein quality. From a nutritional and human health perspective, the key driver is absorbed utilisable amino acids, not ‘total protein’. The metrics matter.

Conclusions

- Animal-based proteins have an important role in providing balanced nutrition for humans.

- Animal-based proteins are not only important for dietary amino acid supply, but also for the supply of critical vitamins and minerals.

- Animal-based proteins have superior protein quality and nutrient availability, which needs to be considered in any discussion of sustainable food production.

- For developing countries, protein quality must be considered when evaluating population dietary protein supply wherever total protein intake is close to the requirement.

- For Western-type diets protein quality must be considered wherever energy intakes are low, i.e. diet/weight loss, elderly, performance sports, illness.

- Protein quality must be considered when comparing the environmental footprints of protein foods.

- The focus should not be on plant-based or animal-based foods, but on plant and animal, to provide diverse, balanced, nutrient-rich mixed diets.

- Animal-based proteins are a costeffective source of many essential nutrients for humans, including amino acids.