News & Advice

Single super is clever choice for future carbon target

New Zealand research in the 1970s and 1980s found that even wellmanaged ryegrass/white-clover pastures in New Zealand were nitrogen (N) deficient.

Tactical use of N fertiliser from early spring to late autumn showed that good pasture responses were achievable. However, from the 1990s, year-on-year increases in national N fertiliser use indicated a move away from the reliance on clover N fixation to provide N for pasture growth. Particularly in irrigated dairying, N-fertilised grass pasture was easier to manage because its growth was more predictable than clover-based pasture, with less yearly variation.

The Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Freshwater) Regulations 2020 have now set a cap on N fertiliser applications on grazed pastoral land – essentially no more than 190kg N/ha annually. For those farmers currently exceeding this cap, changes to their farming systems, subtle or more complex will be required to maintain productivity. One of these possible changes will be the reintroduction and management of legumes such as white clover in their permanent pastures.

Double benefits

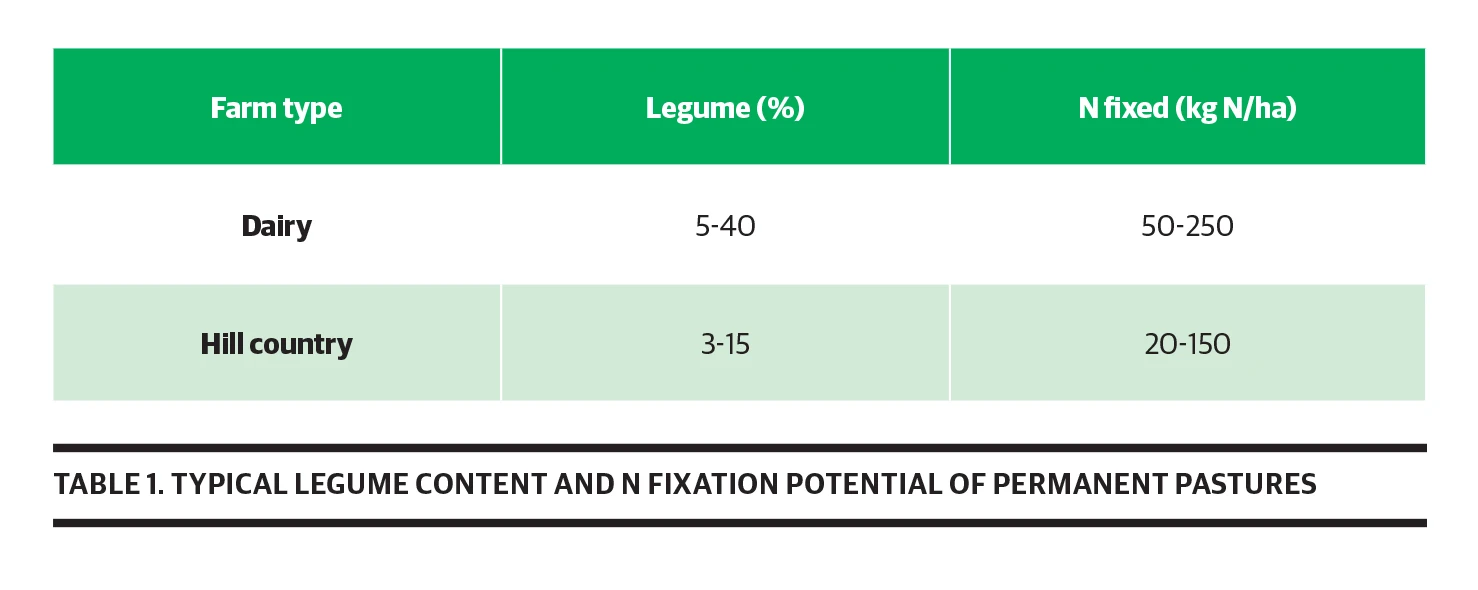

Legumes provide very high-quality feed for animal production, as well as making a major contribution in N supply to the farm system through their symbiosis with Rhizobium spp., infecting legume roots and forming nodules that ‘fix’ atmospheric N into N compounds they supply to the legume. Legume N fixation varies seasonally and between years associated with fluctuations in clover growth. DairyNZ past research indicates that around 25kgs of N is fixed per 1000kgs DM of legume. The amount of N fixed per year ranges depending on legume content and function as indicated in Table 1.

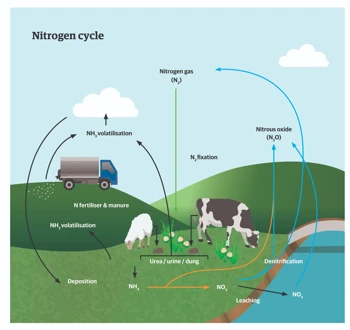

The N fixed by legumes reaches the soil to build up the N pools and is cycled by various routes. Grazing animals eat the legume and return a high proportion of fixed N to the soil in dung and urine.

Nitrogen also returns through death and decay of any uneaten above-ground plant material and roots. The N returned to the soil in this way adds to the system and becomes available to the grass in the pasture through the decomposition actions of micro-organisms in the soil.

Over the last 20 years or so, legumes seem to have been disadvantaged in our intensive dairy systems by grazing management practices more suited to the grass component of the mixed sward, pasture pests (clover flea and clover root weevil) and soil compaction, wet winter and dry summer conditions).

Adjusting grazing management to better complement the legume component of the sward will help better support nitrogen efficiency.

Getting the best out of your clover/grass pastures

Farmers grow legumes, most often white clover, in association with a variety of grasses and herbs. In comparison to the associated species, white clovers are less able to explore the soil volume for nutrients and water because of genetic limitations to their root systems. Not all legumes are affected by this though, as lucerne and red clover are deeper-rooted than white clover. To optimise the growth and function of the clover and grass associations, decades of research on soil fertility management in New Zealand has been developed. This has revealed that phosphate (P), potassium (K), sulphur (S), trace elements (particularly molybdenum and boron) and lime are essential for good legume growth and N fixation.

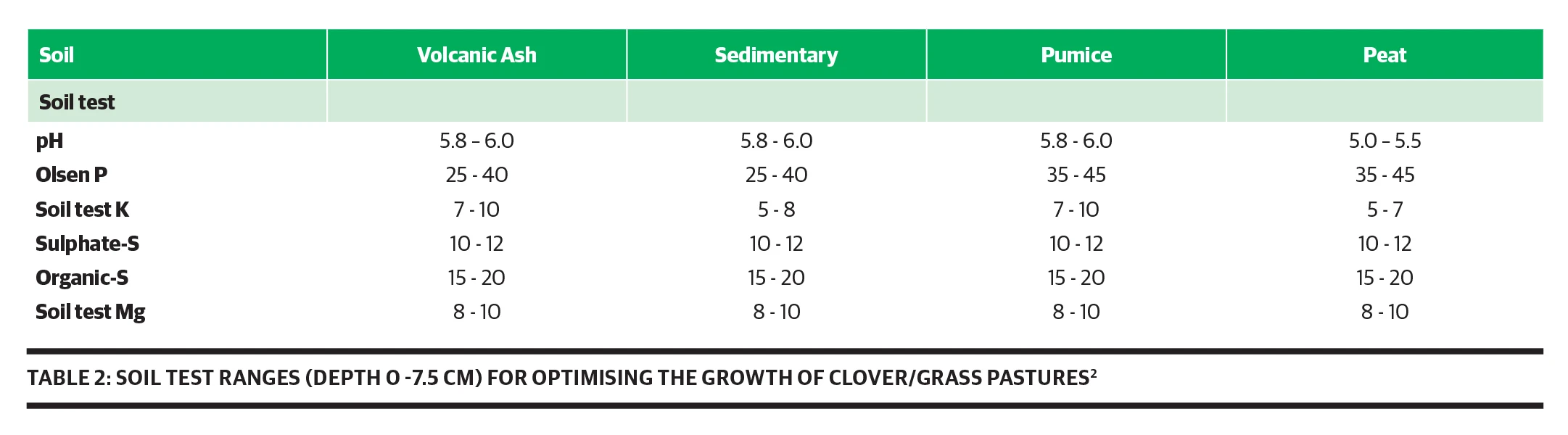

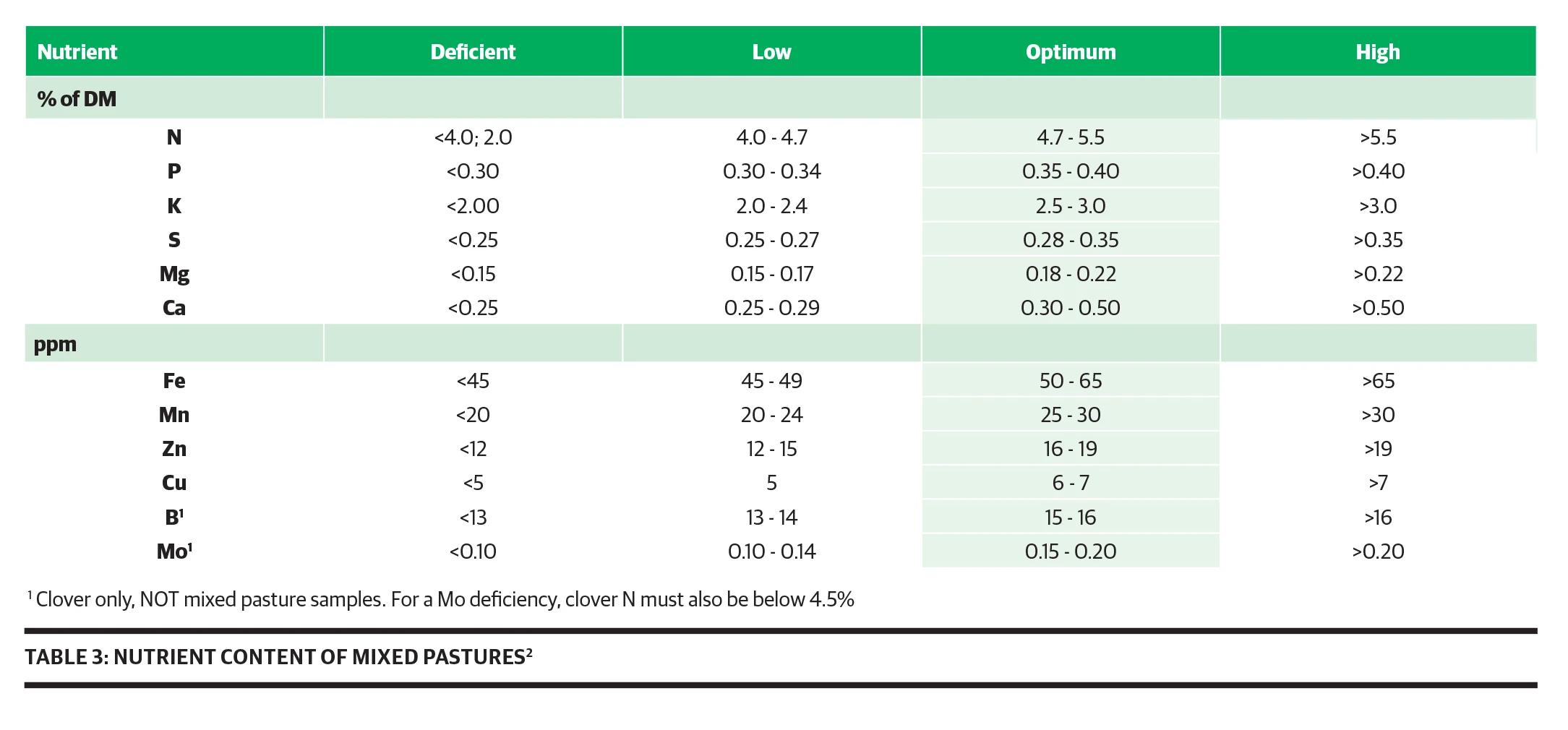

For optimal performance, a combination of natural soil nutrient supply, plus fertiliser nutrients and lime are required. Optimum nutrient levels for different soil types are shown in Table 2 (opposite page). Pasture samples, when the pasture is actively growing and not limited by moisture or temperature, should also be regularly monitored to ‘fine tune’ the fertiliser nutrient programme, especially for trace elements.

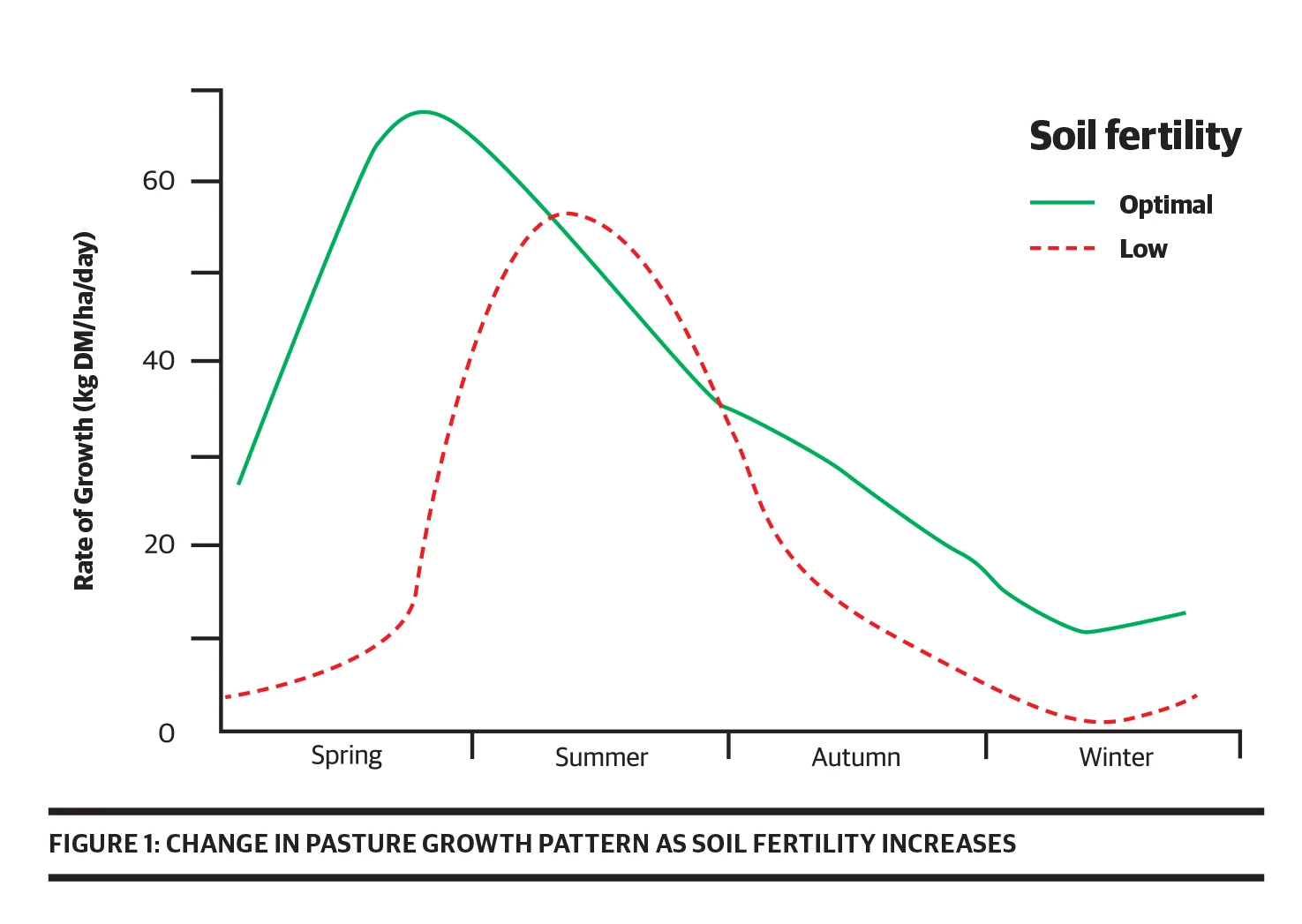

Managing soils and pastures to achieve these levels of fertility encourages the legume component of the sward to grow better, which increases biological N fixation and an eventual increase in the soil N pool. This transforms a farm’s pasture growth curve from the low fertility curve to the high fertility curve depicted (Figure 1). The consequent increase in pasture production and quality between the low and optimal fertility production curves means that in the latter case more capital stock can be carried through winter, allowing for a higher stocking rate, earlier lambing and calving and later drying-off.

There are, however, periods of the year when N fertilisers, used strategically, will increase pasture production and profitability. Care should be taken when using N fertiliser on clover/grass pastures because for every kg per ha used, clover N fixation is reduced in the short-term by about 0.3kg N/ha1. However, tactical N fertiliser use will not reduce the amount of legume in the pastures provided pasture management is good.

Establishing clover in your sward

When we look at our pastures, we nearly always overestimate the legume content. A top performing pasture needs about 30% of its dry matter (DM) produced in legumes to supply enough nitrogen to maintain high pasture production and good pasture quality. However, most mixed legume/grass pastures in New Zealand will have less than 10% legume on an annual basis.

There are various reasons why the legume content of our pastures is less than desired, primarily because most farmers in New Zealand have a “grass” mentality and most legume content is compromised at establishment.

To achieve satisfactory legume content there should be more concentration on the following:

- Higher sowing rates

When it comes to permanent perennial ryegrass pasture seed mixtures, they have a higher sowing rate of grass compared to legumes. Sowing 20kgs/ha of a diploid perennial ryegrass is equivalent to sowing 1,000 ryegrass seeds per square metre (broadcast) or 125 seeds per metre row (drilled). - Sowing depth

The other common mistake when establishing white clover is that it gets sown deeper than the 30mm required. It is important to keep the seed as close to the surface as possible. - Timing of grazing

Ryegrass establishes much faster than legumes so timing of first grazing is also important. The first three or four grazings should be quick and grazed to lower residuals, remembering the aim is to set up the new pastures for the next five to six years, not to maximise herbage production in the first three months. Establishing a new pasture is a considerable financial outlay, so make sure all pasture species sown are given the opportunity to germinate, survive and contribute to the overall production over a long period.

There are many instances of very high performing legume-based pastures across all regions in New Zealand. The benefits to be gained from increasing the percentage of legumes in pastures include improved summer/autumn pasture quality and free nitrogen, allowing farmers to achieve the new targets set, so they’ll find it well worth the extra effort.