News & Advice

News

15 December 2025

Two Rural Icons, One Shared Paddock: Ravensdown Partners with Footrot Flats

![Market Outlook Summer 2026 [Thumbnail Squared] (1)](/media/asjpyowg/market-outlook-summer-2026-thumbnail-squared-1.png?width=640&height=426&format=webp&quality=90&v=1dc6a1838d450b0)

Reports

11 December 2025

Market Outlook Summer 2026

News

05 December 2025

Christmas store hours

News

25 November 2025

Applications open for 2026 Hugh Williams Memorial Scholarship

News

12 November 2025

Superphosphate stands the test of time

News

28 October 2025

Our stores are open for business

Governance

23 September 2025

Ravensdown South Island shareholders have voted Jane Smith to the Ravensdown Board for a three-year term.

19 September 2025

Market Outlook Spring 2025

12 August 2025

Director Elections 2025 – South Island Area election

News

05 August 2025

Robotic Rolleston Lab will Boost Farm Soil Testing

News

31 July 2025

Ravensdown 2025 financial results

Governance

28 July 2025

Board of Directors Election 2025

News

23 June 2025

Kate Faulks reflects on her path to the Ravensdown Board ahead of 2025 Director Elections

Expertise

23 June 2025

Core Governance attributes for a Ravensdown director

News

09 June 2025

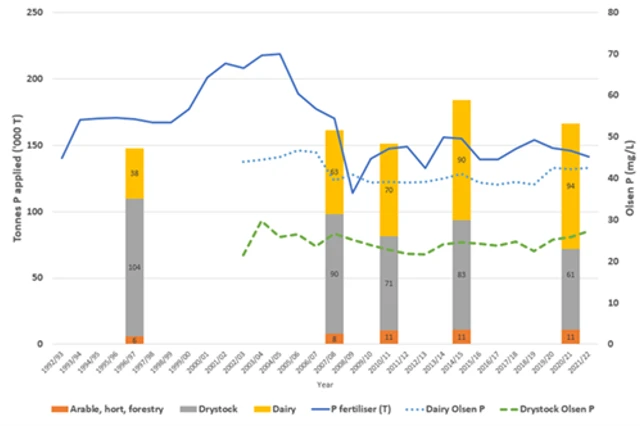

HawkEyePro Launch

Expertise

04 June 2025

Market Outlook Winter 2025

News

03 June 2025

Friends of Ravensdown - Fallgate Farms

News

26 May 2025

Where Are They Now? – Ravensdown Hugh Williams Memorial Scholarship

Events

15 May 2025

Young Farmer Grand Final

Events

12 May 2025

Lawrence Lions Club Winter Crop Competition

Research & Innovation

01 May 2025

Fonterra invests in EcoPond pilot to reduce on-farm emissions

Events

01 May 2025

Fieldays

News

23 April 2025

Where Are They Now? – Ravensdown Hugh Williams Memorial Scholarship

News

01 April 2025

Where Are They Now? – Ravensdown Hugh Williams Memorial Scholarship

Publications

12 March 2025

Friends of Ravensdown: Mac Hops

News

06 March 2025

Where Are They Now? – Ravensdown Hugh Williams Memorial Scholarship

News

05 March 2025

Lifting the lid on governance

News

20 February 2025

Where Are They Now? – Ravensdown Hugh Williams Memorial Scholarship - Georgia Higinbottom

News

03 February 2025

Friends of Ravensdown: Foxtrot Home

News

29 January 2025

Scholarship winner ready to get scientific with farming

News

13 December 2024

Friends of Ravensdown: Floating Peaks

News

01 November 2024

Gearing up for Freshwater Farm Plans

News

23 September 2024

Kate Faulks elected to the Ravensdown Board

News

09 August 2024

Ravensdown delivers solid financial performance in challenging environment

News

27 June 2024

Better Bags

News

31 May 2024

Harald Hendel appointed Aerowork CEO

News

29 May 2024

Graham Stuart appointed to Ravensdown Board

Expertise

23 May 2024

Dealing with drought conditions

Expertise

16 May 2024

Cadmium: The facts

News

24 April 2024

Share up for maximum benefit

News

02 April 2024

2024 Director Elections

News

14 February 2024

‘Scary’ floods inspire scholarship winner to improve rural climate resilience

News

30 January 2024

Ravensdown Rocks with Shed Solution

Expertise

14 December 2023

Testing method unlocks healthy soil

News

14 November 2023

Ravensdown’s Agri-Women take it to the Next Level

News

25 July 2023

Ravensdown is reducing its greenhouse gas emissions with low-carbon urea

News

19 June 2023

Tangaroa Walker named Ravensdown Agricultural Communicator of the Year 2023

Expertise

13 June 2023

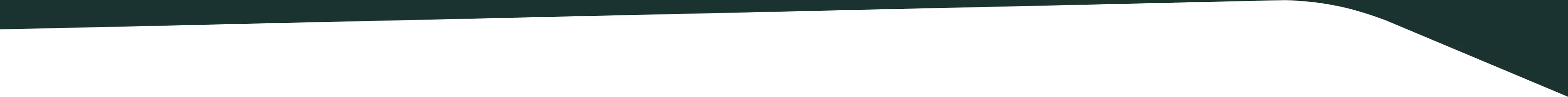

Trends pointing to productivity risk for New Zealand

News

26 April 2023

Agnition on a mission

News

05 April 2023

JV makes debut investment in emissions reduction tech

News

03 April 2023

New Ravensdown tech helps farmers map and respond to slip damage

27 March 2023

Fertiliser Association launches revised Code of Practice

News

22 March 2023

Ravensbourne Wharf upgrade completed

03 March 2023

Cyclone recovery for farmers

Expertise

03 February 2023

New 10 in 7 milking regime shows benefit for staff

Research & Innovation

03 February 2023

Genetically modified crops - do we need a rethink?

03 February 2023

Sub-surface irrigation helps improve water-use efficiency

02 February 2023

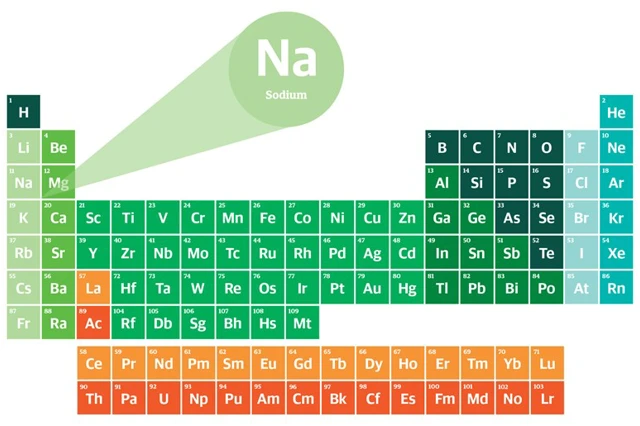

Elementary essentials 7: Sodium

31 January 2023

Bridging the gap between science and farming

Expertise

01 October 2022

Elementary essentials 6: Calcium

Expertise

09 August 2022

The importance of having legume in your permanent pasture

08 July 2022

Animal Welfare Considerations

Expertise

09 February 2022

Is Molybdenum deficiency holding your clover back?

News

07 February 2022

New EcoPond tool a game changer for methane emissions

Expertise

07 February 2022

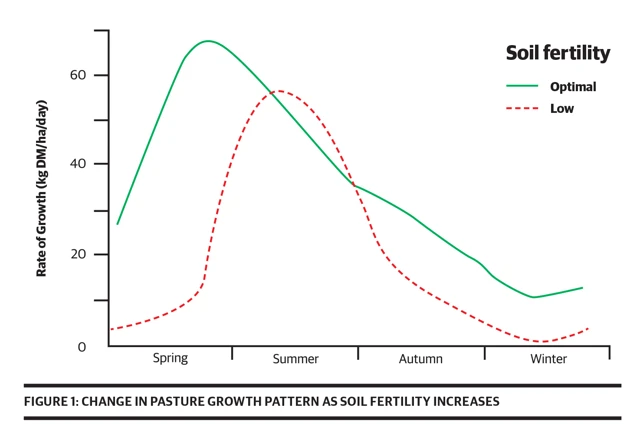

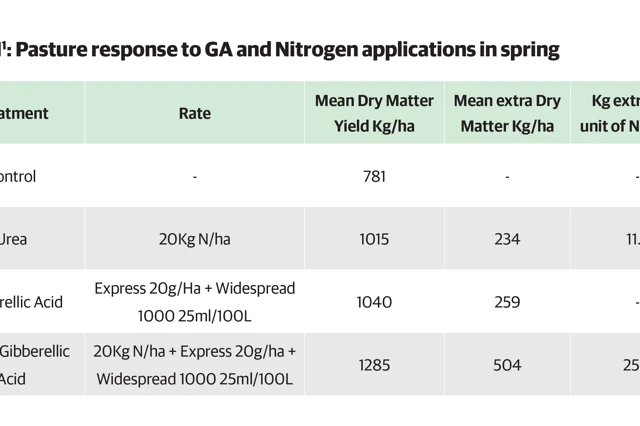

A formidable combo: Liquid N and gibberellic acid

Expertise

07 February 2022

New tool to measure soil mineralisable nitrogen

Expertise

27 September 2021

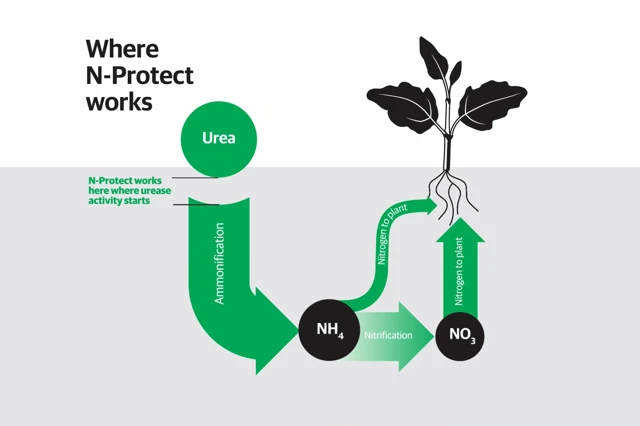

N-Protect – the smart choice in coated urea

Expertise

16 September 2021

Elementary essentials 5: Magnesium

19 August 2021

Ready. Select. Grow. Nitrophoska Select

Expertise

09 August 2021

Elementary essentials 4: Sulphur

Expertise

09 August 2021

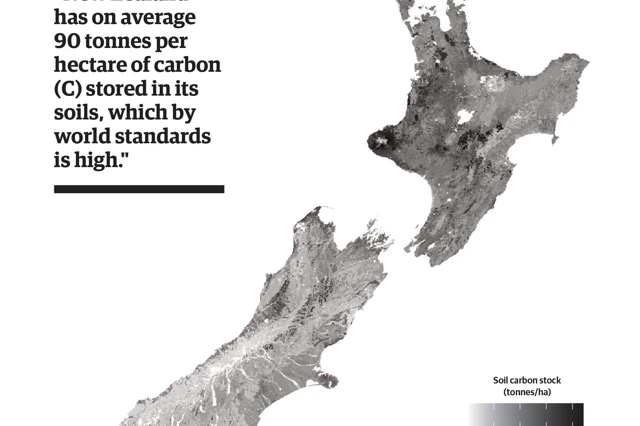

New Zealand’s carbon soil stocks: what do we know?

Expertise

01 July 2021

Elementary essentials 3: Potassium

Expertise

01 June 2021

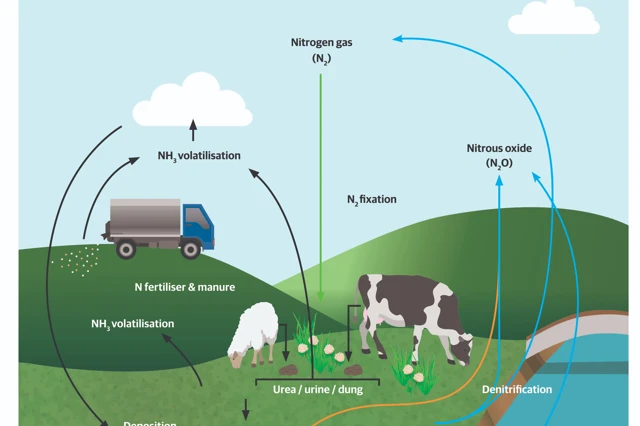

Elementary essentials #1: Nitrogen (N)

11 May 2021

Superphosphate ideal for spring spreading

Expertise

04 May 2021

Elementary essentials 2: Phosphorus

Expertise

15 February 2021

Don’t run fast to stand still

Expertise

18 October 2020

Beating the insect pests in forage brassica crops

Expertise

05 August 2020

Superphosphate – phosphate with benefits

Expertise

05 August 2020

Liquid nitrogen as an option

Expertise

26 May 2020

Winter Maintenance important for quality and persistence of Lucerne

Expertise

18 July 2019

Shining the spotlight on potash

Expertise

27 November 2017