News & Advice

Elementary essentials #6: Calcium (Ca)

The alkaline earth metal calcium (Ca) is the twentieth element in the periodic table and is one of the 19 elements essential for life in all higher plants and animals on planet Earth. Calcium is the fifth most abundant element in the Earth’s crust at 3% and the third most abundant metal.

Discovery of Ca Calcium compounds, such as calcium carbonate and gypsum (calcium sulphate) have been used by humans for millennia. Lime as a building material and plaster for statues has been used since 7000 BCE. Depending on your age, you may even remember using Plaster of Paris (aka gypsum) to make your own craft models. The first recorded lime kiln, discovered in Mesopotamia, dates to 2500 BC. Around the same time gypsum was being used in the Great Pyramid of Giza and in the tomb of Tutankhamun. The ancient Romans used calcium oxide as mortar, after heating limestone and driving off the carbon dioxide (although they did not realise that is what they were doing).

Pure Ca metal, as with magnesium (Mg), was first isolated in 1808 by Sir Humphry Davy in England. He used electrolysis on its oxide. Sir Humphry named the element after the Latin word calx, which means lime. Like Mg, Ca metal does not exist in nature as it reacts spontaneously with water and only occurs naturally as compounds in association with other elements.

Why is Ca essential?

Plants

Calcium is a secondary nutrient required in large quantities in plants for structural components of cell walls and membranes and as an important counter ion (to balance electric charge of anions inside cells). Calcium also acts as a messenger inside cells to promote enzyme activity and plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses.

Animals

Calcium is highly important in animals because it builds the endoskeleton (bones) and teeth of vertebrate animals and the exoskeleton of invertebrates such as shellfish, crayfish and crabs. Calcium is also essential for muscle and nerve function.

The vital role of Ca in agriculture

Soils with adequate Ca levels generally have better structural qualities, are more friable and better aerated and drained. A principal reason for this is that Ca bound to soil colloids ensures that the colloids flocculate (bunch together) more easily, leading to greater soil porosity. As such, gypsum is known as a soil “conditioner” that can displace too much sodium (Na) in saline and sodic soils and assist flocculation in some heavy clay soils. Agricultural limestone would be a cheaper form of Ca to apply for this purpose but also raises soil pH, which may not be required. It should be noted that it is primarily the carbonate in agricultural lime that increases soil pH not the Ca ions, as some commentators insist. If Ca ions were responsible, then gypsum would also increase soil pH, which it does not.

While absolute Ca deficiency is relatively rare in nature (because of the relative abundance and availability of soil Ca), excessive Ca in calcareous soils restricts plant growth and development. New Zealand pastoral mineral topsoils generally contain between 1,000 and 5,000kg/ha of plant available Ca.

Plants, particularly horticultural crops, may show Ca deficiency symptoms even in soils with high Ca content. Symptoms of deficiency include death of growing points, premature shedding of blossoms and buds, tip burn, blossom-end rot and bitter pit. Calcium is supplied throughout the plant in the xylem and plant Ca cannot be remobilised and supplied to the growing points of developing plants.

In animals, without an adequate supply of calcium over the long term, teeth, vision and brains are damaged, and bones become brittle (osteoporosis). Given all these roles, it is no surprise that humans and other animals need a lot of Ca, as it forms about 6% of body weight, ignoring water content.

There have been no recorded Ca deficiencies affecting grazed legume/grass pastures in New Zealand and so calcium fertilisers per se are not usually recommended, although Ca is applied as a companion element in superphosphate (20% Ca), lime (39% Ca), dolomite (23% Ca), gypsum (23% Ca) and other derivative products, which helps replace Ca lost in product, transferred to nonproductive areas of the farm, or leached as a counter ion.

Farm animals, particularly lactating females, can suffer acute Ca deficiency disease, i.e. hypocalcaemia. This may be despite adequate soil and hence pasture Ca content. This metabolic disorder can be precipitated post birth as lactation starts and the dietary requirement for Ca triples. The feed intake of Ca may not be adequate to meet this greater demand and the animals mobilise bone Ca. This mobilisation of bone Ca requires adequate Mg availability in the animal and a number of factors can act singly or collectively to prevent adequate remobilisation of bone Ca.

Environmental impacts

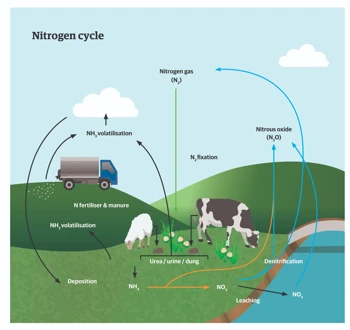

As a divalent cation, Ca2+ is relatively strongly bound to the negative charge on soil colloids and not very mobile. However, Ca does preferentially leach as a counterion to balance the electrical charges in soil as nitrate and sulphate anions leach in drainage water. While there are no known environmental issues with Ca, the principles of the 4Rs (right place, time, rate, and form) for fertilisers and lime containing Ca should still be followed.

Written by Dr Ants Roberts