News & Advice

Don’t run fast to stand still

Dairy farmer, Ravensdown shareholder and Fonterra board member Leonie Guiney and her husband Kieran are passionate believers in New Zealand’s pasture-based farming system, envied by many overseas. Leonie shares with us how we need to utilise this system in times of rapid change.

With the new National Environmental Standards (NES) rules placing a first-ever input cap on farmers and with other rules such as winter grazing, Leonie says it is time to return to what New Zealand farmers do best – maximising the use of our pastures first.

“We’re an island at the bottom of the world, blessed with a fantastic rainfall environment to grow pasture,” Leonie says. “What’s amazing about New Zealand farmers, accentuated by my time in Ireland with subsidised farmers, is that we figured out how to turn pastures into protein customers want and run sustainable farm businesses despite exposure to commodity cycles. And we are the best in the world at doing it.”

Clover-based pasture farming is integral to keeping New Zealand’s system simple and profitable enough to ride the market cycle lows. Leonie explains that we’ve been setting our stocking rates and calving and lambing dates to match the way our environment grows for decades. For those who were tempted away by the push to increase production, a return to a pasture-based system can reduce their reliance on high inputs that chase production rather than profit. “We’ve developed fantastic ryegrass and clover pasture systems in New Zealand, but we have regressed to chasing output, which increases operating costs and demands more infrastructure investment until some are running faster to stand still. In this mode farmers get trapped in a cycle of ever-increasing investment, convincing themselves they need to increase outputs to ‘spread the overheads’.”

Leonie and Kieran started farming in 2002 (contract milking). A Wellington city native, Leonie was always interested in farming’s positive economic impact, which saw her go to Massey University to study agricultural science. This is where she found her inspiration for simple pasture farming systems from lecturer Dr Colin Holmes.

“Dr Holmes was a rare scientist with a deep understanding of how to link science, pragmatism and economics to create resilient farming businesses in the New Zealand climate,” Leonie says.

Her inspiration and respect for New Zealand dairy farmers was cemented when in Ireland, where she realised just how unique our ability to farm with the environment really is, and with family and lifestyle being a core value for Kieran and her, the New Zealand dairy industry’s ability to build equity was a huge drawcard for the couple. With a combination of a strategic plan, luck, risk-taking and a relentless focus on simple, replicable low-cost systems, they were able to build equity fast. Using the cyclical nature of the industry to their advantage the Guineys now own seven farms, (five dairy and two run-offs - three of which are 50:50 equity partnerships) but they have been very specific about how they've done it.

“We buy pasture curves, rainfall and soil types and we target a return on capital that delivers a safe margin over interest costs or we don’t buy,” Leonie says. “It took us a long time to find an environment we wanted to live and farm in, where the land was at the right price that we could get a good return on it.

"In a pasture system you are farming a pasture curve that cycle proofs your operation. That gives us confidence that we can survive the lows and then benefit significantly on the highs.”

Leonie says it is unsustainable and unnecessary to increase inputs to a level where profitability only occurs on upcycles. “Chasing more milk to spread overhead costs is like being on a mouse wheel. More feed requires more concrete to utilise the feed better, there's more effluent to handle, bigger machines to harvest and so on.”

The couple chooses to run systems that don’t demand constant reinvestment in depreciable infrastructure.

“Producing less milk is not something to be ashamed of. Our farms consistently produce less milk per average cow in Canterbury, but our EBIT per hectare is consistently higher and our stress levels are lower. Profitable simple systems allow investment in things like planting for environmental outcomes that are a win for the environment, our business and our brand.”

The Guiney way

The Guineys currently have 3,760 cows (3.5 cows per ha) milking over five of their farms. They have focused on offering a pathway for young people in the dairy industry and as a result have recruited a number of 'fabulous young couples' onto their team. Two couples are 50:50 sharemilking, another two are lower order sharemilkers and they have a single contract milker on their home property, otherwise known as their ‘training ‘ farm. Only one of the farms fed any supplementary feed last spring and that’s because it was purchased in June without their system’s target autumn-saved pasture on hand.

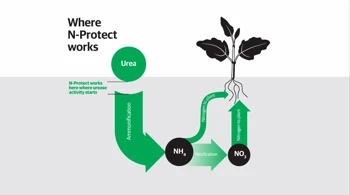

When using a ryegrass clover pasture, nitrogen can be used strategically to fill deficits in early spring and later into the autumn, as throughout the main growing season the clover provides nitrogen fixation and more protein than ryegrass.

The often-overlooked fact is that New Zealand soils require phosphate to maintain clover, which also maintains the ryegrass. “Phosphate is in the milk we send off the farm and we have an obligation to replace that in our soils so our clover can fix N again.

We need to understand what our soils need to maintain optimum nutrient levels to have optimum pastures. To not replace your outputs is called mining and it is economically illogical as well as inappropriate,” Leonie says

“Clover needs access to light to persist in the sward, so in a high input system where you are shutting up a lot of paddocks to grow silage it means you are shading out the clover and therefore need to apply nitrogen rather than the clover supplying its own. You then need to harvest the silage with tractors and store it, which is more cost, time and mess, when the cow and the clover can do that job for you at much less cost.”

When it comes to genetics, Leonie says they don’t focus on a cow that can produce a whole lot of milk, such as a Holstein Friesian, but one that can perform for them in their environment.

“We use a Kiwi cross because we need her to calve once every 365 days. If we need to fill her with supplements and breeding aids to do that then it’s not a good investment.”

Unintended NES consequences

While the ‘190 cap’ on nitrogen won’t impact the Guiney family’s farm systems, Leonie is concerned about the approach that has been taken in using “blunt tools” such as input controls.

“I say embrace the ‘190’ because we can make that work, but we should not accept input controls.

"Real expertise sits on the ground with the farmer, so the best outcomes are achieved when policies and standards are designed in partnership. We all want the same outcomes for the environment, and we should be measuring and targeting them together.”

Leonie expects the crop sowing requirements being imposed on farmers will certainly have unintended consequences. For the Guineys the new rules would mean that instead of fallowing their ground after a winter kale crop to preserve moisture they would need to sow another break crop (e.g. oats), which would simply reduce the available moisture and the potential yield of the next kale crop.

For dryland farms, this is a big problem as they are farming moisture as much as the crop. Leonie says it would also require more passes with tractors to harvest the interim crop, burning diesel and adding more cost, then storing the feed to only feed it back out again with tractors due to the kale crop yield being impacted!

“This is an example of a blunt tool trying to achieve a single goal, while misunderstanding the bigger picture, a biological system,” she says. “This isn’t to ignore the N-leaching risks, but policy that forces intensification and more use of diesel and machines seems completely counterintuitive. Our ecological systems are balanced for our environment, and our cows, which are designed to harvest feed all by themselves, with good legs and a harvester on the front.”

Leonie says the rotational grazing systems scientists and farmers have developed over the past century allow us to compete with our products internationally, and it is on-farm efficiency, via clover-based pasture systems, that underpins that competitiveness.

“It’s really unfortunate, as both policymakers and farmers have the same goals, but these are the unintended consequences of not working together.”